The theory of Quantum Computing operates based on four postulates or axioms, i.e., self-evident truths. Though nothing about them was self-evident to me. But they are pretty simple, at least the first two are, the second two are a bit mind-bendy, but that’s quantum computing for you.

Postulate 1: Quantum System as a Complex Vector

This postulate says that the state of a quantum system can be represented by a complex vector, i.e., a bunch of complex numbers. That’s it. A single qubit is a quantum system, so we can represent it with a complex vector. A multi-qubit computer is also a quantum system so we can represent that too with a complex vector, albeit a longer complex vector than the single qubit one.

I love this postulate because now I can stop trying to imagine how the physics of this stuff works, and operate in the pristine realm of math. I know vectors and Linear Algebra, and I am ok with each number in the vector being a complex number. No, seriously I am cool with that.

Postulate 2: Observable Quantities as Matrix Operators

A quantum system can have a bunch of properties we can measure. The classical analog of these properties for a classical system can be weight, temperature, volume, etc. This postulate states that any such measurable property for a quantum system can be represented as a matrix operator. To make life really easy, these operators are Hermitian, i.e., they are equal to their conjugate transpose. Not only that, their eigenvectors form a complete orthonormal basis of the quantum system’s vector space.

This postulate is like a cherry on top of Postulate 1. Now, any time I want to poke and prod a quantum system, which remember can be thought of as nothing but a bunch of complex numbers, all I need to do is multiply it by some matrix. And not any matrix, but a particularly convenient class of matrix at that!

Postulate 3: Measurements

When we measure a quantum system, i.e., apply a matrix operator to a complex vector, we will get one of the eigenvalues of the matrix as our reading. And the quantum state will collapse into the corresponding eigenvector.

There are a number of concepts we need to unpack here. First, lets clarify what apply means. Think of it as a two step process, first we get a reading, like the kind of reading we’d get on a multimeter, and second the quantum state being measured changes to some other state. The only possible readings we can get are the eigenvalues of the matrix operator. This is the first weirdness of this postulate. Lets say I have a matrix operator whose eigenvalues are +1 and -1. Then regardless of the quantum state I am measuring, I’ll always get one of these two values. But all is not lost, the probability of my getting a reading of +1 or -1 depends on the specific quantum state being measured. The second weirdness of this postulate is that some quantum states change when they are measured, i.e., to say that after measurement the old vector can no longer be used to represent that state, we have to use some other vector to represent it. And this other vector is always the corresponding eigenvector of the eigenvalue we measured! So why did I use the word “collapse” in the above paragraph? Because, after this first measurement, subsequent measurements will not cause the state to change. It is said to have collapsed to its ground state. For any easy introduction to this postulate read my blog post on Quantum Measurement for Beginners.

Postulate 4: Time Evolution of the System

A quantum system left to itself, will keep changing over time. This postulate states that we can get the future state of the system by multiplying the current state with a Unitary transformation matrix. A Unitary matrix is one whose inverse is equal to its conjugate transpose.

Conclusion

In this post we saw the four postulates of quantum computing. These are stated in different order in different text books, but the essence remains the same. These four postulates are:

- A quantum state can be represented as a complex vector.

- Physically measurable quantities of some quantum state can be represented as Hermitian matrix operators.

- When we measure a quantum system with an operator, we get one of its eigenvalues as the reading, and state collapses into the corresponding eigenvector.

- A Unitary transformation matrix can be used to derive the future (or past) state of the quantum system.

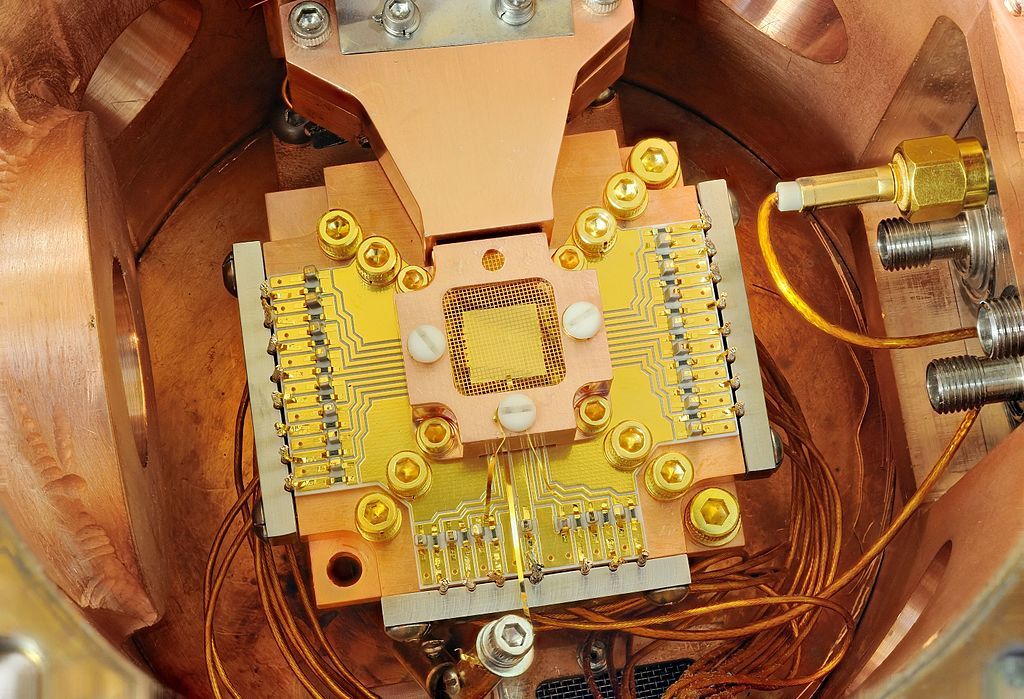

Image from National Institute of Standards and Technology / Public domain